These are just a few examples of the responses I get when I talk about storytelling at birthday parties. And about the storytelling training courses I teach.

Do you have similar questions?

In this article, I will discuss the three basic ingredients of a story.

So you’ll better understand what storytelling means, and how you can use it yourself.

Storytelling makes your topic interesting and urgent

But first, let’s zoom out a bit.

Why would you use storytelling in the first place?

You use storytelling because people have a soft spot for stories. Including managers, finance experts and policy advisors.

A story makes your message interesting, coherent and urgent.

A story helps people with creating a mental picture. They better understand your message, become curious, emotionally engaged and inspired. As a result, they are more likely to take action.

Storytelling: you already do it

Want to use storytelling in communication about your work?

This may feel like something radically new.

But it isn’t: you already do it.

Everybody tells stories. Also at and about work.

About how an idea for a new product emerged during a daily run, for instance. About that time the electricity went down at the lab. About the inside joke that colleagues hid in a memo.

For storytelling, you don’t have to start from zero.

You start with your own natural ability.

Then, you build on this ability with storytelling techniques. To make better use of it, and do so more consciously.

To do this, you tap into techniques that have been used for ages, in various forms. From myths and fairy tales to Hollywood movies and games.

Stories have 3 main ingredients

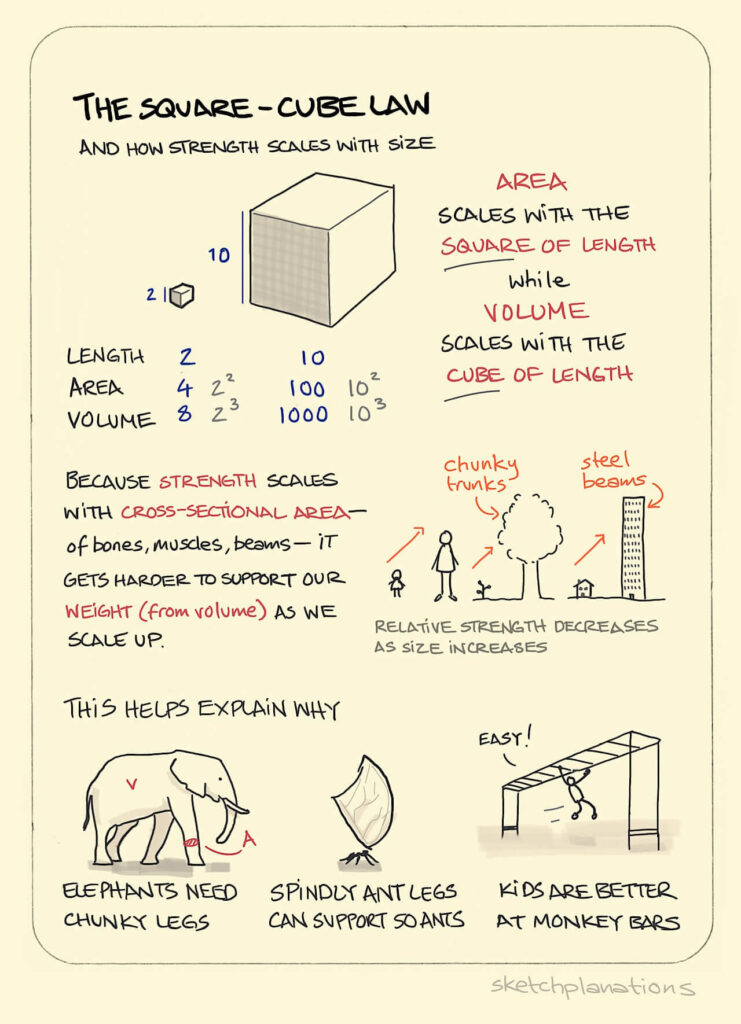

A story contains roughly 3 main ingredients: a main character, a narrative arc, and scenes.

Main character

Stories are (mostly) about people.

About their motives, goals, emotions and problems.

Therefore, telling a story is easiest when you use characters. They can be real or imagined.

A classical story has one main character. Next to this protagonist there are other characters, who help or oppose the main character.

With a main character, you add perspective, direction and cohesion to the story. And it enables your audience to sympathize.

In a story about your topic you can, for instance, choose one particular citizen, customer or patient as a main character.

Your protagonist could be Ingmar, a 32-year old freelance graphic designer.

He has a few small and one big client: a pet supplies store.

Ingmar likes to spend his free time road cycling and mountain biking. He spends a lot of money on it.

Narrative arc

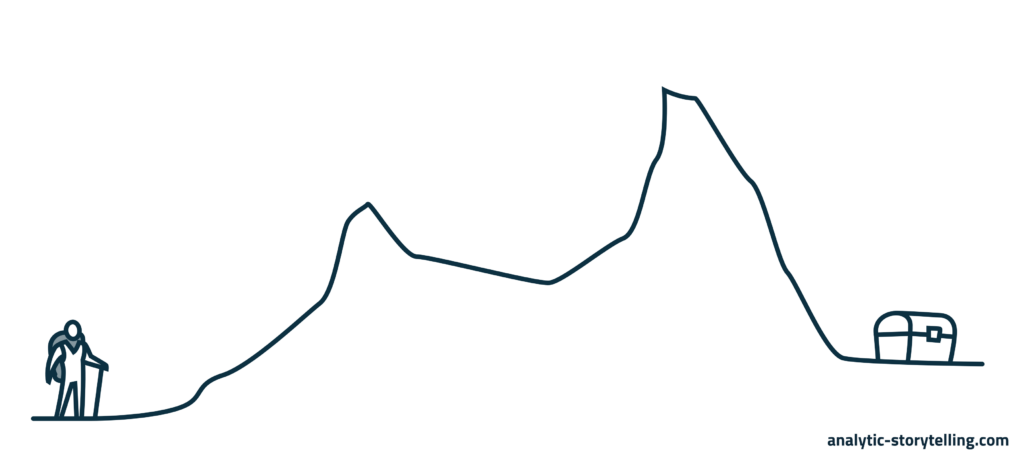

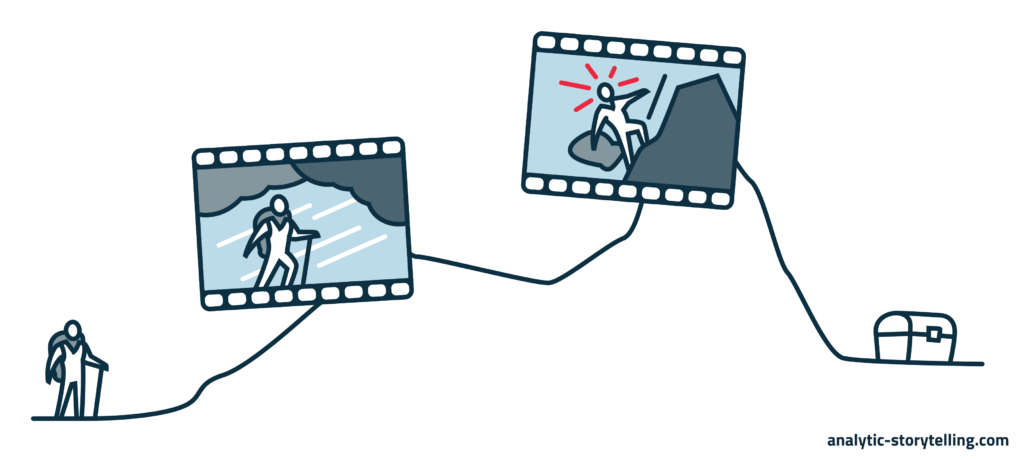

The second main ingredient of storytelling is a structure in which tension first rises towards a peak and is then resolved. Or, in storytelling jargon: a narrative arc.

A narrative arc has a more or less fixed order.

In the beginning, the audience gets to know the protagonist (or the topic), and starts to get involved.

In a movie, this is often a kind of ‘24 hours in the life of…’

But merely getting to know the main character or topic, and getting involved, is not enough.

To keep the audience interested, something has to happen. Something has to be at stake.

Only then it becomes a story.

For this reason, the main character is usually given a goal. Or a problem to solve. In The Lord of the Rings, the goal is to destroy the Ring in Mount Doom.

The goal sets the story in motion and creates tension. It creates a gap between where we are now and where we want to go. And there are multiple obstacles on the road.

At the end of the narrative arc, the tension is resolved.

A classical ending is a ‘resolution’, a solution: the Ring is destroyed, the lovers find each other, the murderer is arrested.

So what could a narrative arc in your professional communication look like?

As a financial advisor, you may say that controlling your own money is important. It ensures that you can do what is important to you, like living in a nice house or taking a cycling trip.

But many people do not have a realistic idea of their finances. Graphic designer Ingmar is an example. He has a large student loan debt, is optimistic about his business prospects, and is always buying new cycling gadgets.

This is risky. For instance, with a few setbacks he may fall into debt, stress out, pile debt upon debt and, eventually, for instance, lose his house.

The solution is a website where people can test how healthy their financial situation is. Someone like Ingmar answers questions about revenues, spending, savings and loans. He then receives a score and advice. For instance, to create a buffer.

Scenes

The third and last main ingredient of storytelling is the scene.

A scene takes place at a particular place, on a particular time. A scene usually contains people, sensory details and action.

A scene helps the audience create a mental image and immerses them in the story.

The opposite of a scene is a summary.

A summary is, for instance: in the years that followed, the couple had three children.

In a scene, you zoom in on the two oldest children who come to see their newborn sister. You describe how their eyes twinkle and how they carefully stroke her cheek. And how, a little later, they suddenly jolt the hospital crib in a higher position, because they were curious what would happen when they push a button.

In a scene in your professional communication, you describe, for instance, how Ingmar opens an email from his biggest client.

The pet supplies store has gone bankrupt. They can’t pay the bills he sent them.

Ingmar just bought a new gravel bike – an offroad racing bicycle. He takes it for a ride to process the news.

He cycles down a hill at high speed. At the bottom of the hill there is a cattle grid. He lightly turns his handlebar to take the turn. Then he feels his wheel slipping.

He falls. He screams. In his right arm – he is righthanded – he feels a sharp, burning pain. Probably broken.

Two seconds later he thinks: shit – my insurance deductible. And how can I work now?

More storytelling, or less?

Characters, a narrative arc, scenes…

You can use all of these together to improve your communication. If you do, you have a complete story.

But even if you use only one of the three ingredients, it makes a huge difference.

For instance, if you structure your policy plan with a recognizable introduction, a complication and a resolution. Or if you start your blog post with a short anecdote: a scene.

How you use storytelling depends on your audience, your goal and what medium you use. And on what you feel comfortable with.

My advice: experiment. Life is too short for boring presentations and texts.

Want to know more?

Want to know more about storytelling? Or want to use it in your own work?

- Read more about our storytelling method.

- Sign up for our weekly Analytic Storytelling tips.

- Ask us to collaborate on your storytelling project of -training

Priscilla is director, advisor and trainer at Analytic Storytelling. We help people make content-driven stories.