I will address these questions in two articles. In this first article I discuss why your message can benefit from a main character. I also share some examples of protagonists in content-driven communication.

Why using a main character is effective

A nice first example of content-driven communication with a main character is the animation Joined-up care, Sam’s story. In the 3.5-minute video, the audience gets an idea of what integrated care means, through the story of one patient. This video nicely illustrates the three ways in which a story can benefit from a main character.

First advantage: Your audience can picture your topic

The video’s main character is Sam, an 87-year-old man who suffers from emphysema, Type 2 diabetes and arthritis. Thanks to Sam, the audience can right away picture the patients concerned, which is much less the case with commonly used policy terms like ‘vulnerable elderly’ or ‘multimorbidity’. That kind of abstract jargon is used in every sector. Because such terms are not visually evocative, they are much more difficult to process for our brains.

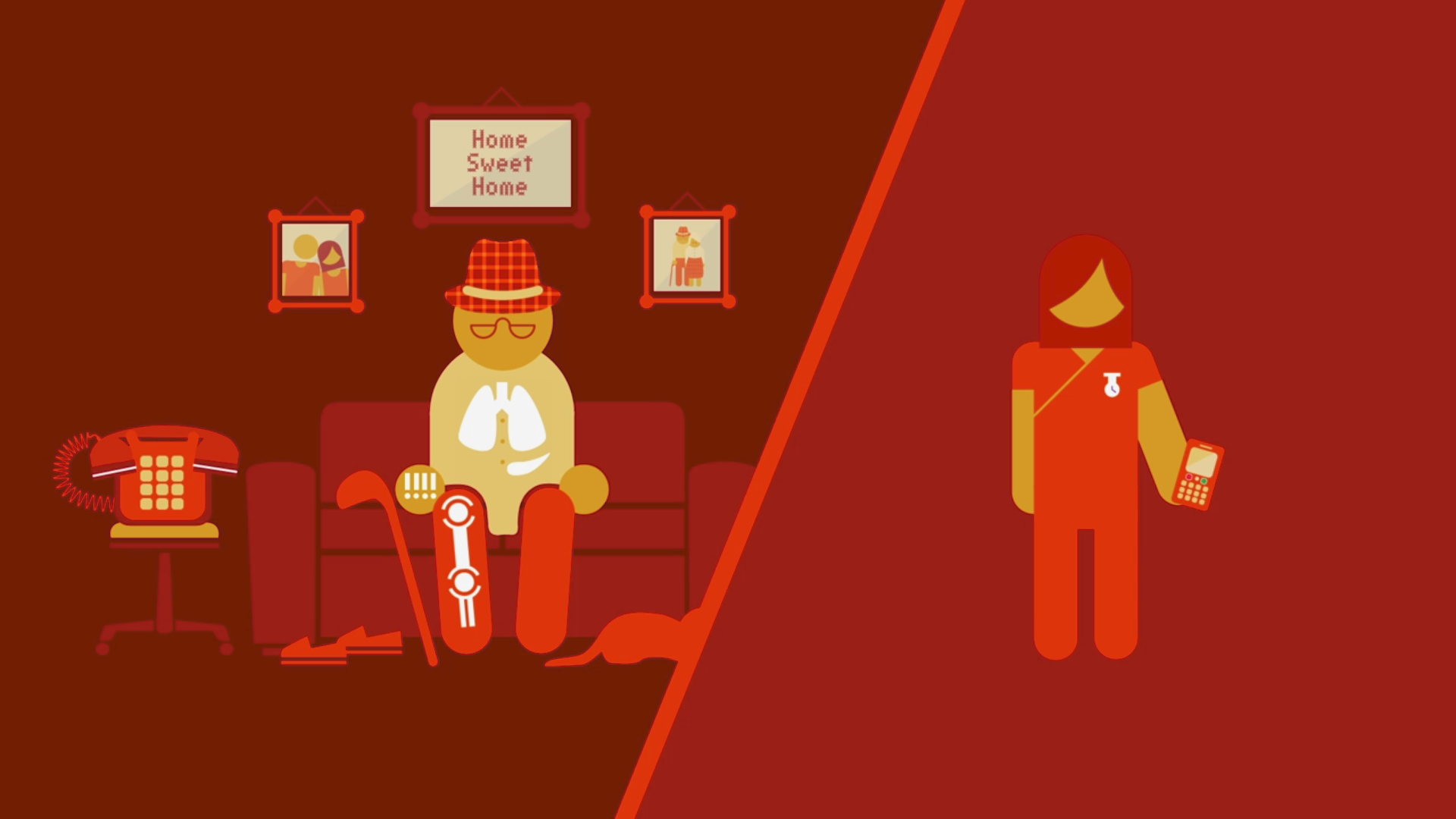

Via the main character, other people enter the story, like district nurse Cathy and a volunteer who takes Sam to the shop every week. Again, this is a more effective way of communicating than by using abstract concepts like ‘primary care’ and ‘informal care’. In addition, the main character brings in all kinds of other tangible details. Think of the chair in Sam’s shower, the oxygen cylinder and the medication dispenser. All these images make it easier for your audience to understand and remember your message, and make that message more appealing to them.

A main character also automatically locates your story in a specific time and place, and adds mini-scenes. These too help your audience process the information.

Second advantage: the audience empathises

Because a story with a main character has one perspective, the audience experiences the story from this perspective. This happens at the beginning of the story, for instance, when Sam is struggling with the death of his wife and feels lonely and depressed. He finds it difficult to discuss all his symptoms in brief consultations with his GP and sometimes panics and calls for an ambulance. Six months and many hospital visits later he moves to a nursing home. Next, the audience is drawn into an alternative, integral care scenario, in which Sam is provided with a coordinator. Sam can continue to live at home, because district nurse Cathy is there to answer all his questions.

While Sam’s story is no Titanic, it still gives the viewer a sense of relief to see that Sam is doing better. Terms like ‘increasing quality of life’, ‘living independently’ and ‘patient-centred care’, although commonly used, are less likely to evoke such feelings. When the audience gets emotionally involved in the story, it will process the information much more easily.

Complex topics are often about large numbers of people, so it may feel a little odd to focus on one single character. But it is really important to do so if you want your audience to empathise. Our capacity to empathise decreases rapidly when applied to large numbers. We feel relatively little emotion when confronted with the fact that there are 65,3 million refugees worldwide, but we are very moved by a story about one Syrian child who is forced to leave his home. Even when a story is about two people rather than one, our relative empathy decreases.

Third advantage: your audience is motivated by your ‘why’

The introduction of a main character also puts more emphasis on the goal of your story. In the end, your policy, complex product or research has to have value for people. In the case of Sam’s Story, an integrated care policy makes it possible for people to live an agreeable life at home, even when they’re ill.

In communication lingo this goal is called the ‘why’. Simon Sinek, who introduced this concept, argues that it is the why of a story that determines whether people will be inspired and motivated by it. When they are, and they believe in the same goal as you do, they will be willing to change their behaviour. They will vote for your policy plan, invest in your product or work hard for your change management plan.

A lot of content-driven communication places a heavy emphasis on the hows and the whats. Obviously, you have to mention these too. For instance, in the video, what allows Sam to live a pleasant life at home is the fact that budgets are joined and his dossier is accessible online. But the story becomes much more compelling when you put these hows and whats in the context of a central why. When you use a lead character, this happens almost automatically.

Five examples

A video about healthcare is relatively well-suited for a main character. Animations more often feature characters than texts do. And healthcare policies have a direct impact on the lives of people. Still, in many other types of communication, and in many other sectors, stories can improve when you add a character. Much more often than you might think. Here are a few examples, for inspiration:

In this Dutch leaflet Anna tells us about how her life in 2035 is affected by changes in housing, healthcare and technology. The story is interlaced with first-person story fragments by Wouter, an independent care coordinator. To eleven pages of narrative, another five are added that explain the trends that were already illustrated by the story. So in this publication, the narrative element is even more prominent than in Sam’s story.

Comic: On a plate: A short story about privilege

Like animation videos, other types of visual communication are also suitable for using main characters. Actually, it can be quite hard to make a good visual story without them. This comic explains the meaning of the abstract concept ‘privilege’, by telling a story about two characters, Richard and Paula. Richard’s parents are rich, Paula’s are poor. We see how little initial differences lead to Richard and Paula ending up in very different societal positions. So in this case, there are two main characters.

Exhibition: Wealth of waste (link leads to content in Dutch)

This exhibition introduces the audience to 18th century recycling methods, through the story of a factory owner and inventor, Watse Gerritsma. His story illustrates how, during the Industrial Revolution, experiments in chemistry were connected to entrepreneurship, resource policies and waste management issues. Museums and books often feature protagonists, to bring history to life.

Watse Gerritsma, de main character of the exhibition Rijk van Rotzooi of the Fries Museum. (Image: Studio BrandendZant / Jona Kuijs)

Presentation: Feats of memory anyone can do

In his TED-talk about ‘feats of memory’, Joshua Foer is his own main character. He describes how he got interested in memory championships and decided to participate in one himself. He uses his own experiences in this strange world to explain how our memory works.

Commercial: Google Search: Reunion

You can explain how Google’s search functions work, one by one, but you can also show them in passing, while telling a story. That’s what this commercial for Google India does. It’s about a reunion between an old man in India and his childhood friend in Pakistan. The video strongly appeals to the emotions, which resulted in millions of views. Commercials often feature main characters, and often subordinate technical details to storytelling. As a knowledge worker, you will usually opt for a more informative approach, but this video nicely illustrates how far you can take character-oriented storytelling.

There are, of course, many more ways to use main characters in content-driven stories. Charitable organisations use characters so you will empathise with children in development countries, and news media and newspapers use them to bring abstract facts to life.

Next time: 10 tips for using characters in your story

If you think using a main character in your communication about your topic might be a good option, then of course the next question is: how do you do this? In a follow-up article I share ten practical pieces of advice on how to tell stories with a main character.

Arnaud is trainer, advisor and text writer at Analytic Storytelling. He helps customers to send out a clear and convincing message in both words and images.

Arnaud is trainer, advisor and text writer at Analytic Storytelling. He helps customers to send out a clear and convincing message in both words and images.