You have two guests in your restaurant who have just ordered the main course. They tell you they would like to have a glass of wine with that. What do you do?

Either: You bring them the wine list with all the wines that you have in stock, which specifies grape, age and a taste description for each wine.

Or: You suggest a wine that matches the dish they have just ordered.

- You bring them the wine list with all the wines that you have in stock, which specifies grape, age and a taste description for each wine.

- You suggest a wine that matches the dish they have just ordered.

Always ask yourself first: what does my audience want to do with this information?

Of course, there is no general rule for what to do in this situation. It depends on how you would answer this question:

How does my audience want to use my communication?

Are your guests opinionated wine connoisseurs, the kind of people who enjoy exploring wine lists and who like to choose their wines themselves? Or are they relaxed gourmands who just want a carefree evening and are happy to trust your expert opinion? Perhaps you can guess what type of guests they are, based on your interactions with them. If you can’t, you can always just ask them. When you tailor your answer to their particular wish, their satisfaction is guaranteed.

This is not just true for restaurant owners. Pretty much all communication requires making a similar choice. Each time, the question is:

Does my audience want a lot of raw data, to explore on their own? Or do they want my help, in the form of a more targeted message?

If you tailor your communication to their specific purpose, you help them achieve their goals. Which, in turn, will help you achieve your own purpose.

In this article I will discuss why it is important to adapt to your audience’s goals, and how you can do that. I will discuss some theory and some examples, and I will be using wine list and wine suggestion as metaphors for two different styles of communication. At the end of this article you will find a decision tool for determining the best strategy for your audience.

Wine list and wine suggestion: two styles of communication

If you present your audience with a lot of data which they have to navigate themselves, you communicate in ‘wine list style’. Obvious examples are dictionaries and law codes. Scientific papers also belong to this category. These are sources that your audience explores on its own.

If, instead, you take a big pile of data and select only those parts that are relevant to your audience, your communication resembles the wine suggestion. A legal advisor usually doesn’t present a customer with a list of all legal provisions that apply to his situation; rather, she gives him tailor-made advice on what to do (or what not to do).

What your audience wants determines which communication style you choose

How does my audience want to use my communication? Being aware of the importance of this question is half the work. The other half, of course, is to find a useful answer to this question.

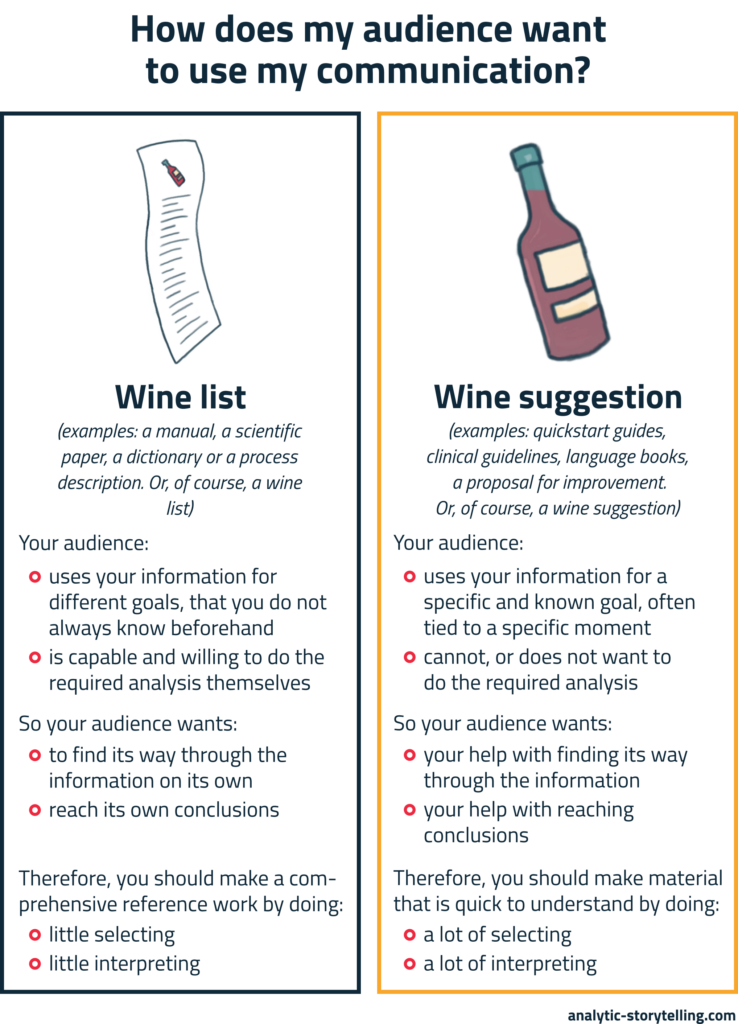

Here’s an overview of the differences between communicating in a wine list and in a wine suggestion style:

It is easier to see the difference when you compare some examples:

Communicating in a wine list style: you provide loads of information, which your audience then has to make sense of

Giving your audience a lot of information that they should interpret by themselves means that your audience has to do a lot of work. It should also possess the required expertise to select and interpret this information. For example:

- A wine list in a restaurant is only useful to guests who enjoy a minute-long exploration of pinot noirs and sauvignon blancs.

- Manuals, for example, those that come with your new television, are also typical examples of wine list style communication. At the time of writing, the author of the manual has no idea who will use it to make sense of the error message on their tv, nor when this will happen. He writes for many different possible audiences and situations. He therefore leaves it to the readers to select information they need, navigating error codes and indexes. That means that the manual has to be exhaustive: it has to include all possible error messages in all languages of the European Union.

- In a scientific article,the results of research should be easy to find, use and reproduce in new scientific research. That is why papers in scientific journals have a fixed format, and also why they are loaded with details about, for instance, research methods and measurements. This makes the articles useful as reference works, now and in the future.

Communicating in a wine suggestion style: you help your audience by selecting and interpreting

You help your audience as best as possible to reach a conclusion from a load of data, by guiding them through that information, and by using your expertise to help them interpret it. For example:

- When you make a real wine suggestion, you select a couple of wines for your guests and you explain why these wines match the dish that they ordered. Your guests know too little about wine or about the dish to do this matching themselves.

- When you buy a new tv, it nowadays often comes with a quickstart guide. This guide explains how you use the tv for the first time, and offers a selection of only those operations that you need to get the tv working. This guide is tailored to a specific audience with a specific goal on a specific moment, namely, someone who has just opened the box and wants to connect the tv as quickly as possible.

- Family doctors work with clinical guidelines. These give them suggestions on, for instance, what medicine to prescribe for an illness. Such guidelines are based on scientific research, the results of which are selected and interpreted by a group of experts, and formulated in such a way that family doctors can directly apply them in 10-minute medical consultations.

Check these 2 real-life examples to see how the same message translates to wine list and wine suggestion style:

Example: memorizing a list of opening hours versus learning one single rule of thumb

Imagine you arrive at the bicycle parking at the train station of Amsterdam Amstel, and you see a sign with these opening hours:

It’s a neat list of days and hours. The sign gives you the complete schedule, wine list style. As a user of the bicycle parking, you conclude whether or not you should stall your bicycle here, taking your travel plan into consideration.

But wouldn’t you be better off with a tailor-made message – with a wine suggestion? I think you would. Look:

You, and 95% of users with you, probably don’t have the kind of broad question (when is this parking open in general?) that requires a wine list. Your question is: can I park my bicycle if I take the first train, and can I still collect it after I have returned with the last train? That’s a typical, specific, wine suggestion type of question. The extra sentence that was added to the sign answers this question by interpreting the opening hours and explaining how these relate to the train schedules.

Thanks to this ‘wine suggestion‘, 95% of the audience immediately sees whether they can and should park their bicycle here. That’s nice, especially when they have to hurry to catch their train.

Still, putting the timetable on the sign was a good idea, as it helps the 5% of the audience that has a different question. Such as: “I have a marathon run that starts at Amstel station this Sunday. Can I put my bicycle in the parking?”.

Example: an orderly policy proposal, part wine suggestion, part wine list

A while ago, we worked with several Dutch municipalities on a policy proposal for child protection. They sent us a 19-page, detailed analysis, drafted by child protection experts. In this document they described in chronological order just about everything that had happened in the preceding years. Plans for the future were interlaced with this detailed analysis of the past.

The analyses were fine. But the way they were presented was not sufficiently tailored to the intended use by their audience. They tried to satisfy two distinct ambitions of the audience at the same time:

- On the one hand, the document had to serve a specific purpose that was clearly defined and tied to a specific moment – a purpose that required a wine suggestion:

- The document had to enable all councillors to quickly decide whether they would vote for or against the proposal in the next council meeting.

- For this decision, councillors would also take into account practical issues like management and finances.

- Councillors didn’t have the time, nor the required background knowledge, for a profound analysis of the dossier. They trusted their child protection specialist to do this for them.

- On the other hand, the document also had to fit various purposes, which could not be fully defined at the moment of writing – a broad goal which called for a wine list:

- Child protection specialists and civil servants in charge of child protection, would be using this document to make various analyses, policy proposals and evaluations, for several years after it was written.

- For this, they needed detailed information about things like current policy, bottlenecks, possibilities for improvement, finances, etc.

We re-ordered their draft so that these two distinct purposes were clearly separated. We started with a wine suggestion style summary that allowed all councillors to quickly get an overview of the plan. In three pages, we answered the following questions:

- How should you read this policy paper?

- Why was this policy proposal drafted?

- What do we want your consent for?

- What’s the main theme of this policy framework?

- How will management and finances be organized?

- Table of contents: Want to learn more?: In the rest of this policy proposal you’ll find the following…

The table of contents offers directions for the reader who is looking for the more detailed, wine list version of the policy proposal. He or she can find their way through the text, at any moment, and draw conclusions that are relevant to his or her specific purpose at that time.

Does it matter what you choose? Yes, certainly:

We often give people a long wine list when all they want is our expert suggestion

Let me emphasize that the choice between a wine list and a wine suggestion type of communication is not a choice between good or bad, or right or wrong. Everything depends on your audience and the situation, which is seldom purely black or white. Oftentimes combining the two communication types is the best solution, as the example of the policy proposal shows.

But I do notice in my work that knowledge workers often reflexively offer a wine list when the situation requires a wine suggestion. We often overdose our audience with information which they have no way of navigating or making sense of. Of course, we almost always do this with the best intentions. But it is not effective. For when the audience doesn’t have the knowledge or resources to make sense of it, chances are they get lost in details, and you subsequently lose them altogether. Which means they will not get your message. If you have ever witnessed lethally boring or incomprehensible presentations, with slides packed with tables and lists, you know how this works.

In the rest of this article I will show you how to make a better, more conscious choice of communication style. I will use 3 examples for this and I will end with a practical decision tool that you can use for your situation.

Curious to know why we tend to automatically offer our audiences a wine list? Check out:

Four mechanisms that push us towards offering a wine list when actually a wine suggestion would be more useful

We have all kinds of reasons, often subconscious ones, to reflexively opt for wine lists. See if you recognize any of these four:

1. We forget to take the question behind the question into account

Imagine your CEO asks you this question: “Could you give me an update about the construction of our new hospital?” It may seem appropriate to give her an hour-long update with a detailed chronological account of the proceeding. But the question behind her question is probably much more practical. This question may be: “When will construction be complete? And will the project stay within the budget?”. In addition, she may have no more than 10 minutes to spare for this update. Therefore, a selection and interpretation of the available information, wine suggestion style, may be a much more fitting response. So don’t be shy to ask follow-up questions when you are not sure whether you understand the task you are given by some decision-maker.

2. We all suffer from the ‘curse of knowledge’

Many knowledge workers spend years studying one specific topic. Whether it’s the laws that govern business takeovers or technical standards for electric cars, you have learned so much about your subject that it is easy to forget that your audience is much less knowledgeable and less experienced. You assume that your audience, like you, can draw its own conclusions from a big pile of information. But how to do this is much less obvious to them than it is to you.

This is what Dan and Chip Heath call the ‘curse of knowledge’ in their book ‘Made to Stick’. As an expert you can’t forget what you know. You are familiar with each detail, every exception, which is why you tend to communicate in a very elaborate and abstract way – in other words, in a wine list style. In their book, the Heaths give an example of designers who invent complicated machines in the computer chip industry. These designers used to draw an elaborate technical drawing for every machine. When the technicians didn’t understand these drawings, the designers made an even more detailed and comprehensive version. What the designers didn’t see was that this made it even more difficult for the technicians to understand the drawings. The designers (and the technicians) were victims of the curse of knowledge.

3. We are not very good at killing our darlings

If you’ve invested a lot of time in something, it automatically feels important to you. Therefore, you want to discuss it. Even if it is actually a side issue or a dead end in your project. These darlings are hard to kill, which means that you are at risk of adding unnecessary details to your story, making it disordered. Your audience will wonder what this has to do with the main message of your story. (Why is grape juice included in the wine list?)

Sometimes it is someone else’s ‘darling’ that’s hard to kill. Organizations often communicate in a way that seems to be designed to keep everyone involved happy: for instance, if a project by department A is discussed, the good work done by department B and C should also be mentioned. The story, bulging with all this extra information, may be comprehensible and familiar to people from this organization, but people from outside will get lost in it.

4. We want our stories to be neutral, objective and comprehensive – and we overdo it

There is nothing wrong with aiming to communicate in a neutral, objective and/or comprehensive way. That is, as long as that aligns with the purpose of your story. But often, these ambitions clash. For instance:

- In an attempt to give an exhaustive overview, you use unfamiliar and vague terms. For instance, you may say ‘in public spaces’ when you mean to say ‘on the streets’, or ‘autonomous vehicles’ instead of ‘self-driving cars’. For you, the first definition may be slightly more accurate, but can your audience still picture it?

- In an attempt to make your text legally correct, you may also make it very abstract. Suppose the Dutch postal service PostNL would use legal definitions in their consumer leaflet about mail delivery. They might end up with something like “‘95% of all mail items in The Netherlands, excluding overseas territories, are delivered from Tuesday through Saturday, with the exception of official public holidays, unless this cannot reasonably be expected of PostNL”. It would probably be more fitting to describe these details in the terms and conditions. Luckily, the leaflet merely states that ‘all domestic mail should be delivered within 1 day’.

The balance between the wine list and wine suggestion styles is best shown through examples. Here’s 3:

Example: how to explain what a pomelo is?

This of course depends on the reason why your audience wants to know. What will they do with the information you give them?

You could give an encyclopedia-style description:

The pomelo, (Citrus maxima or Citrus grandis), is a citrus fruit native to South East Asia. It is usually pale green to yellow when ripe, with sweet white (or, more rarely, pink or red) flesh and very thick spongy rind. It is the largest citrus fruit, 15-25 cm in diameter, and usually weighing 1-2 kg.

Obviously, this is a wine list approach. You are not anticipating any specific ambition that your audience may have with this information. So you present a collection of facts, without selecting or interpreting much. It is up to your audience to draw conclusions from it. The information is correct and precise, but doesn’t really help your audience do something with it.

You could also use an analogy:

A pomelo is basically a supersized grapefruit with a very thick and soft rind.

This wine suggestion approach makes use of the fact that your audience is familiar with grapefruits. This description of a pomelo gives a quick answer to a practical question, such as: ‘this recipe tells me to use a pomelo, but I don’t have one, what can I replace it with?’ As a bonus, the description is shorter and more familiar.

This elegant example is from the book Made to Stick by Chip en Dan Heath. Their message is that, as a knowledge worker, you will often opt for the encyclopedia-style definition. You answer the question in abstracto, but you probably don’t address the practical question-behind-the-question that your audience wants you to answer. The grapefruit analogy is more likely to answer that hidden question. Of course, an even better approach would be to find out why your audience is asking, and to adapt your answer to that purpose.

Example: what does this graph want to tell you about gas use?

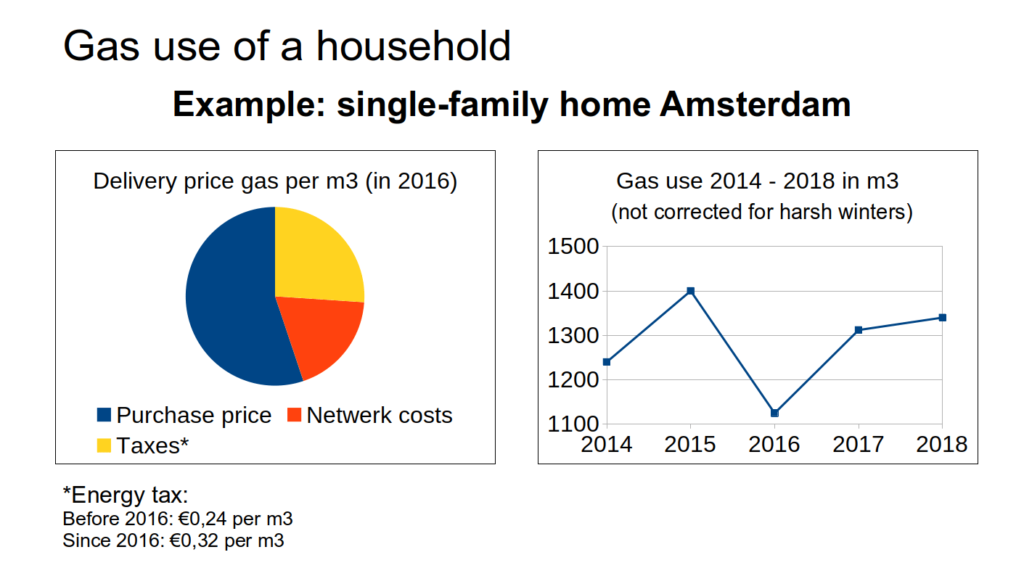

In images and data visualization, there’s also a difference between wine list and wine suggestion communication styles. You probably recognize slides like this one, and perhaps you make such slides yourself: lots of data, but no handles for the audience to use that data. This is rarely effective:

The question is, of course: what did the author expect the audience to do with this information? It is unlikely that this was actually meant to be used as a reference work, wine list style. Presentations aren't really suitablePresentations are meant to verbally transfer information, for example in a meeting or a sales pitch. If you use slides, they should support that verbal transfer. In practice, you are often asked to send around the slides before or after the presentation moment. Usually, that’s not so effective: good presentation slides are not meant to stand on their own, without the story you tell live. Consider making a special reference version. For example by typing out your verbal story in the notes of your slides.for such communication. So they probably tried to convey a more specific message with this. But which?

- That the increase in energy tax has had little influence on gas use?

- That the delivery price in Amsterdam consists of different elements than the price in other cities?

- That single-family homes have fluctuating gas use?

- That more than a quarter of the gas price goes to taxes?

- …

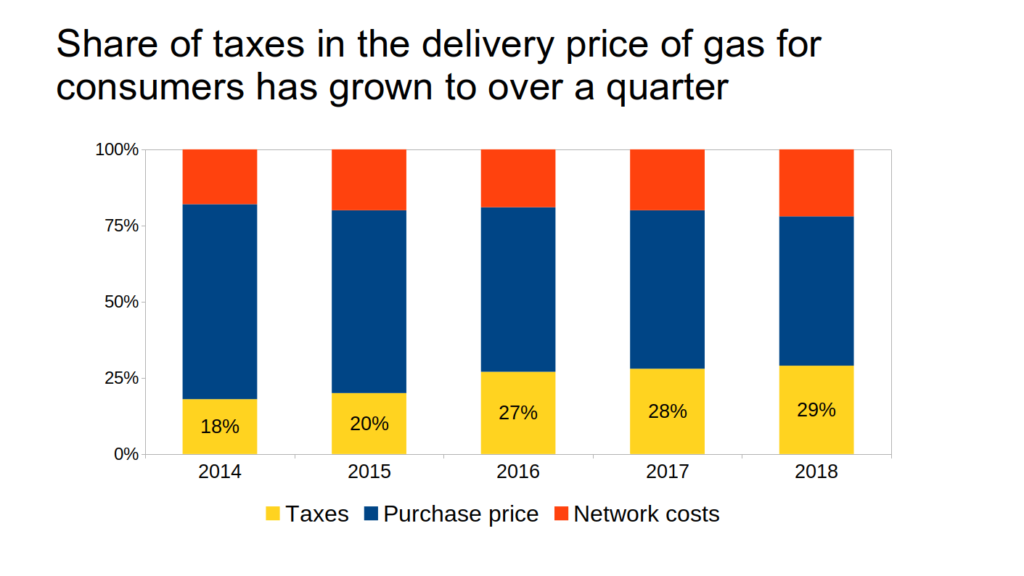

A wine suggestion-approach that effectively communicates that last point could look something like this:

This slide gives a clear interpretation of the data, and presents a selection of that data that supports it. The audience will immediately understand the message, and can focus on your presentation.

Example: what should I do with my new insurance policy?

Imagine you receive a letter from your insurer, which in a typical wine list style does not help you in any way to take action:

Dear Mrs. Sauers,

Please find enclosed the insurance policy document, as requested by you. In this policy you will find the terms and conditions of your insurance. You can keep the policy document with the rest of your documents.

In case your personal situation changes in a way that might affect the insurance, please inform us.

Please do not hesitate to contact us if you have any further queries.

Kind regards,

L. Jansen

The insurer tells you all kinds of details about this new insurance policy document. But how does the letter help you as a reader? Is there still some action required from you, or is all settled now?

Actually, the insurer does want you to do something: they want you to check the document for errors and then neatly file it in your administration. Therefore, it would be better if they write a letter that explicitly tells you what to do, wine suggestion style:

Dear Mrs. Sauers,

Here is your new policy document for your car insurance. Your car will be insured with us for another year. In this letter, I’ll explain what we would like you to do.

What should you do with this document?

Please check your personal information on the document for errors. You can still correct these. If your information is incorrect, it is possible that damage may not be compensated by us. If you find any errors, please inform us. You can find our phone number below. Please file the document carefully; it serves as proof that you have insured your car with us.

Questions?

Should you have any questions, please contact our customer service at 012-3456789. We are happy to answer your questions from Monday to Friday between 8 AM and 8 PM.

Kind regards,

Luc Jansen

The Insurer

This example – which is from this great book, available only in Dutch – shows that the author thought about how the reader would use it: the language is direct and action-oriented, the practical information that you need is easy to find, the headings give you an overview. Note how you can make a difference in your communication on all these levels: word choice, content and lay-out.

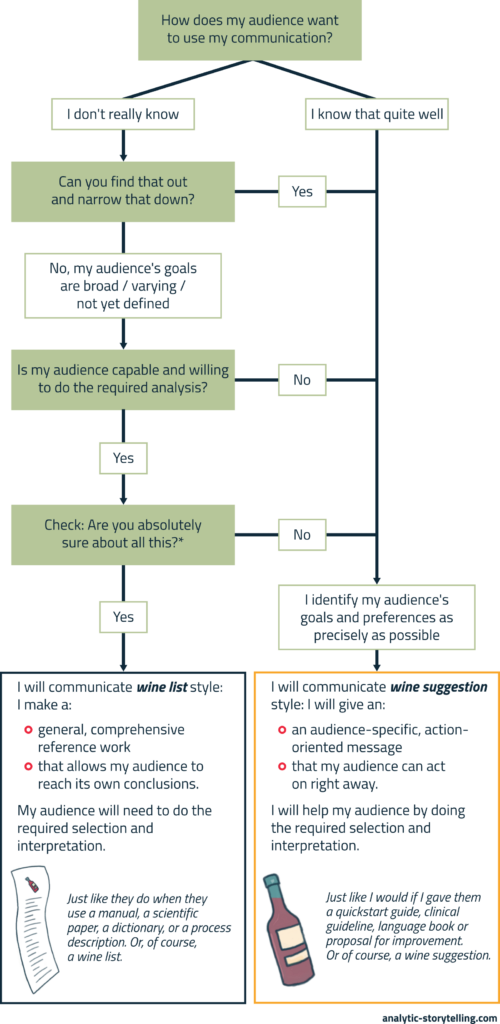

Decision tool: how do I decide whether to communicate wine list or wine suggestion style?

Obviously, it all depends on what your audience wants and needs. Use this tool to decide:

*All too often, we reflexively opt for a wine list when the situation requires a wine suggestion. Check whether you are at risk of doing that. And: talk to your audience to find out about their goals!

Final remarks

Good luck with telling audience-oriented stories – and have fun! If you succeed in making a story that is tailored to the way the audience wants to use it, you help them reach their goals. That’s how you achieve the goals that you set for your communication. Therefore, do make sure you discuss your audience’s wishes as early in the process as possible.

Stijn is director, trainer and advisor at Analytic Storytelling. We help people to make content-driven stories. That is: clear and compelling communication on complex content.