Wil je storytelling gebruiken om beter te communiceren?

Dat kan met de Analytic Storytellingmethode.

Met deze methode maak je in 4 stappen een goed verhaal. Bijvoorbeeld voor een presentatie, een beleidsplan of een subsidieaanvraag.

We hebben de Analytic Storytellingmethode speciaal ontwikkeld voor mensen die over complexe onderwerpen communiceren.

Neem bijvoorbeeld Laura.

Laura werkt voor een ngo. Haar organisatie helpt kleine Indiase boeren.

Laura heeft een sensor ontwikkeld die de vochtigheid van gewassen meet. Daardoor kunnen de boeren het schaarse water efficiënter gebruiken.

Laura gebruikt storytelling om te communiceren met de boeren, lokale beleidsmakers, de ingenieurs die de sensor maken en potentiële donateurs.

Stap 1: Pas je aan aan je publiek

Aan wie vertel je je verhaal?

Voor succesvolle communicatie is het cruciaal om je publiek te kennen.

Je publiek bepaalt hoe je begint, welke vragen je beantwoordt, of en welk jargon je gebruikt en welk perspectief je kiest.

Bijvoorbeeld: leg je in een verhaal over de zorg de nadruk op de onzekerheid voor een patiënt, de werkdruk van een dokter of de kosten voor een verzekeraar?

Je aanpassen aan je publiek is niet het moeilijkste onderdeel van storytelling. Maar het is wel fundamenteel. En in de praktijk gebeurt het vaak niet of niet (expliciet) genoeg.

De Analytic Storytellingmethode bevat allerlei hulpmiddelen om grip te krijgen op je publiek. Maar het belangrijkste is dat je nadenkt over je publiek. En dat je dat doet voordat je aan je verhaal begint.

Laura communiceert deze keer met een Rotary Club in Amstelveen. De leden zijn potentiële donateurs.

Ze maakt een kort publieksprofiel.

De Rotarians zijn goed opgeleid. De meeste hebben een zakelijke achtergrond, sommige een technische. De gemiddelde leeftijd is vrij hoog.

Over India weten ze niet veel. Maar ze zijn breed geïnteresseerd en leren graag nieuwe dingen.

De leden doneren regelmatig aan mensen die dat nodig hebben. Daarbij vinden ze het belangrijk dat hun geld effectief wordt ingezet. Als dat kan zetten ze ook graag hun eigen kennis en netwerk in.

Rotary heeft als uitgangspunt vijf zogeheten Avenues of Service. Twee daarvan bieden Laura een aanknopingspunt: International Service (betrokkenheid bij andere culturen en volkeren) en Community Service (betrokkenheid bij de plaatselijke gemeenschap).

Stap 2: Maak een structuur

Elk verhaal is anders.

Maar goede verhalen hebben ook een gemene deler: een duidelijke structuur met een spanningsboog.

Die zorgt dat je publiek geïnteresseerd raakt en je kan volgen.

In de Analytic Storytellingmethode gebruiken we daarvoor het SCQA-model.

Situation – Complication – Question – Answer.

In de situatie schets je het onderwerp, zodat het publiek erbij betrokken raakt.

Waar gaat het over? Waar bevinden we ons?

Daarna volgt de complicatie met een urgent probleem of een doel. En met hordes die daarbij genomen moeten worden.

Dat leidt tot de vragen: lukt dat? En zo ja: hoe?

Tot slot leg je in je antwoord uit wat jij doet (of wat je publiek moet doen) om de vragen te beantwoorden en de hordes te nemen.

Een SCQA-structuur geeft je verhaal context en urgentie.

Laura maakt een SCQA-structuur voor haar verhaal.

Eerst kiest ze een herkenbaar vertrekpunt voor haar publiek: de Rotary Avenues van International Service en Community Service.

Dan legt ze uit dat de club de afgelopen jaren projecten heeft gedaan in Afrika, Zuid-Amerika, Rusland en China.

Maar niet in India.

Terwijl India na China de meeste inwoners van de wereld heeft.

Ze schetst het beeld dat de meeste buitenstaanders van India hebben: dat van grote, chaotische steden.

Daarna legt ze uit dat het grootste deel van India platteland is. Vol kleinschalige boerderijen.

Dan de complicatie…

Kleinschalige Indiase boeren hebben het moeilijk en zijn vaak wanhopig. De meesten kunnen nauwelijks rondkomen omdat de oogsten mager zijn.

Dat komt onder meer doordat er weinig water is en ze vaak met verouderde irrigatietechnieken werken.

Kan dat anders?

Laura’s sensor zorgt dat boeren gewassen alleen water geven als dat nodig is.

Dat is een heel effectieve manier om de oogst te verbeteren. Effectiever dan alternatieven.

Om het werkende prototype op te schalen zijn donaties nodig. En daar kan de Rotary club bij helpen.

Bijvoorbeeld door een benefietevenement te organiseren samen met de Indiase gemeenschap in Amstelveen. Die is aanzienlijk: in de stad leven bijna 5.000 Indiase Nederlanders.

Er is al een restaurant dat graag wil meewerken.

Willen de Rotary-leden hierover nadenken en Laura mailen als ze interesse hebben?

Stap 3: Wees concreet

Een sterke verhaalstructuur is als een sterk skelet.

Het is nodig om je verhaal overeind te houden. Maar je hebt vlees en bloed nodig om het tot leven te brengen.

Dat doe je door je verhaal concreet te maken.

Dit is juist ook belangrijk bij complexe onderwerpen. Want die bevatten vaak veel abstracties.

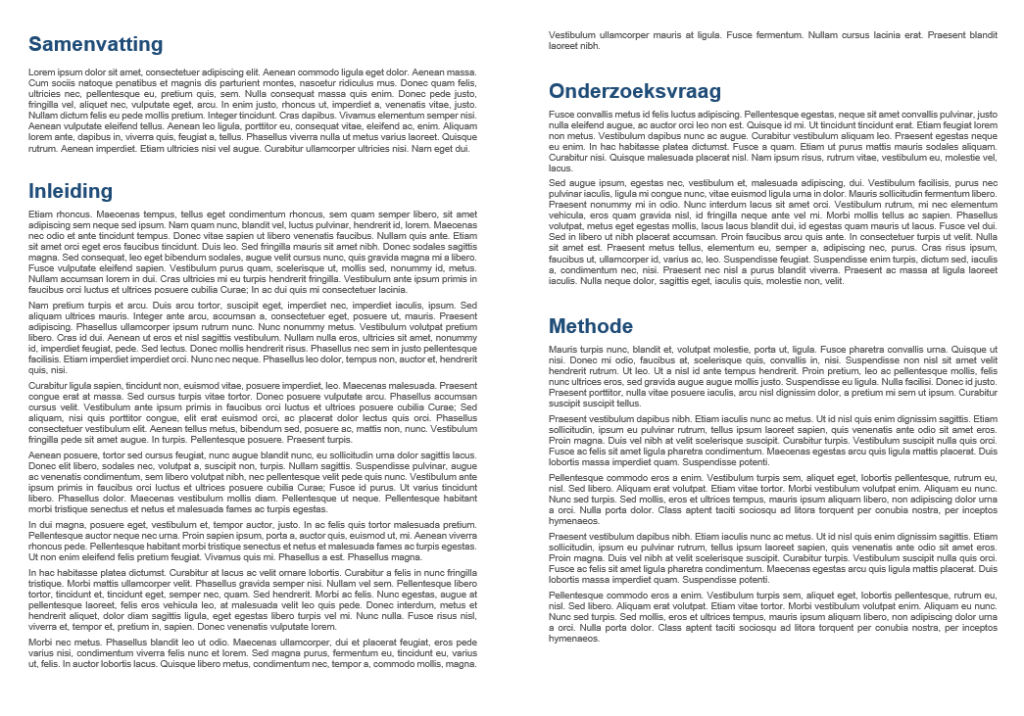

Als je concretiseert, maak je je verhaal zintuigelijk, herkenbaar en specifiek. Je schetst als het ware een (mini)scène die je publiek voor zich gaat zien. Daardoor wordt je verhaal aantrekkelijk, begrijpelijk en invoelbaar.

Concretiseren kan bijvoorbeeld door een voorbeeld, metafoor of anekdote te gebruiken.

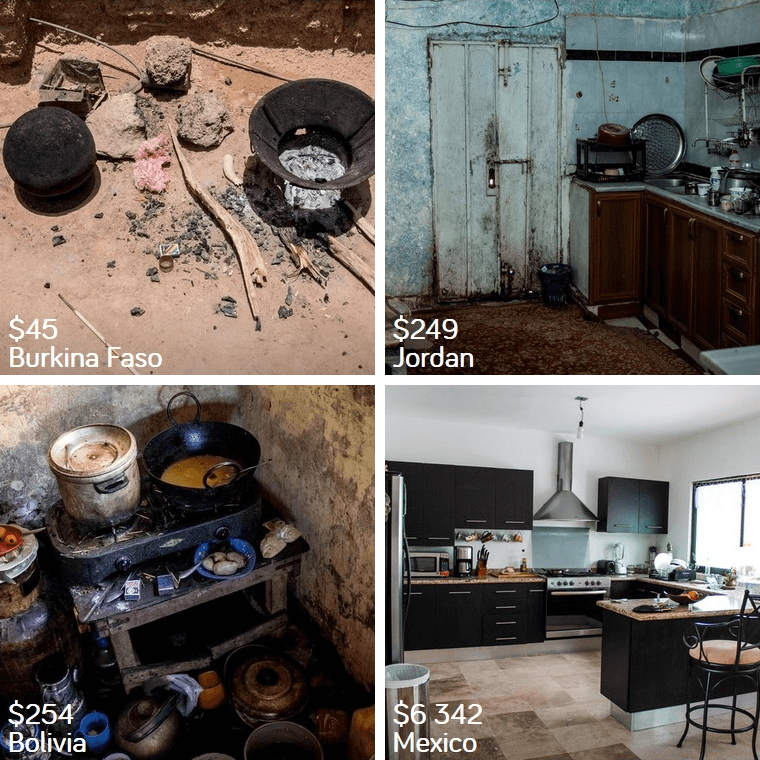

- Laura maakt haar boodschap concreet door te vertellen over wat de kleinschalige boeren produceren. Dat zijn bijvoorbeeld witte kool, aubergines en rozen. Dat doen ze ook voor Nederlandse supermarkten.

- Dat boeren het moeilijk hebben en wanhopig zijn, is een abstractie die niet duidelijk maakt hoe hard hun werkelijkheid is. Daarom toont ze heftige cijfers over de zelfmoorden als gevolg van hun uitzichtloosheid. In 2019 waren dat er gemiddeld 28 per dag.

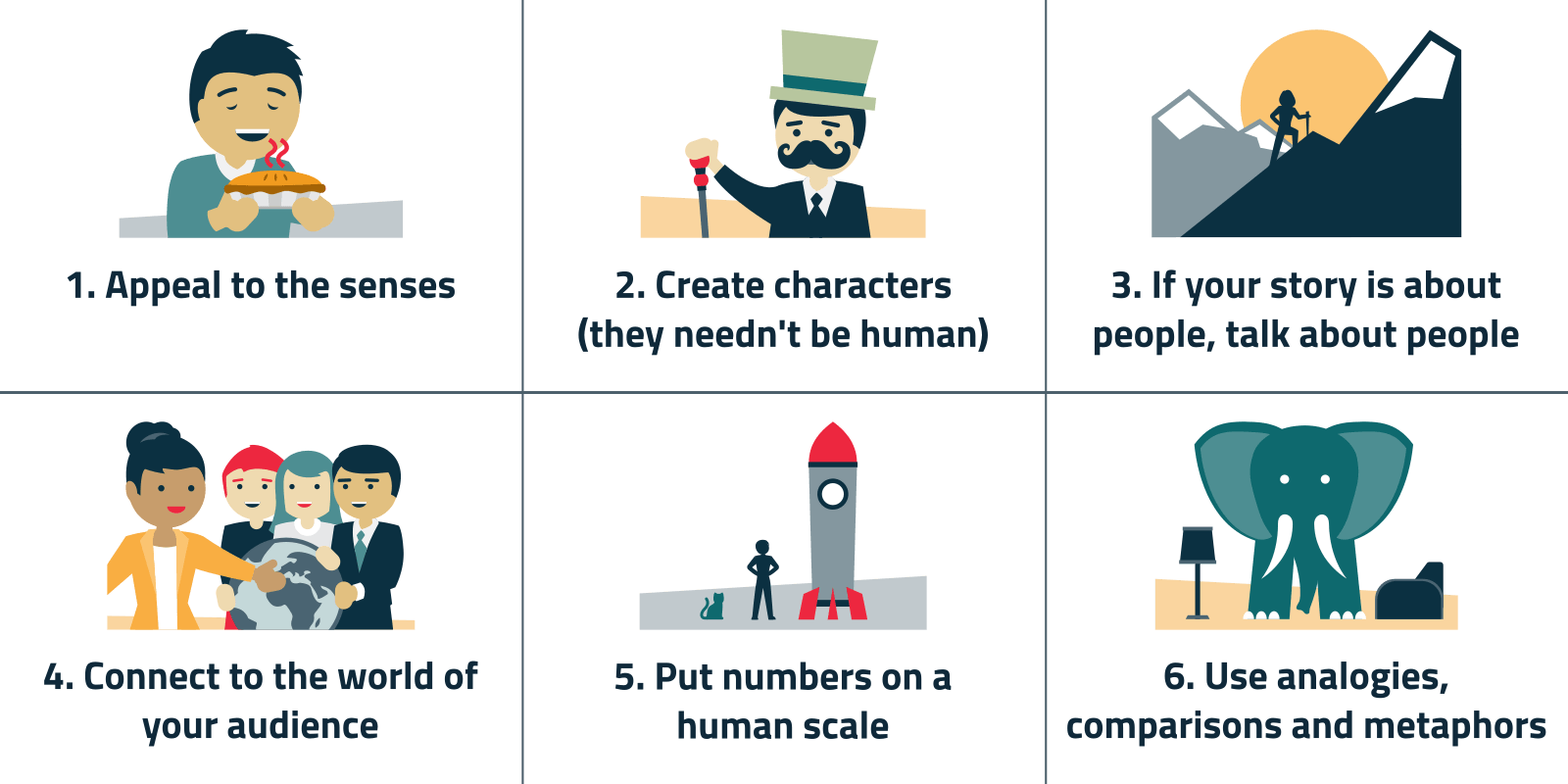

- Ze introduceert één boer – Vyaan – die ze recent heeft ontmoet. In het droge seizoen houdt hij met andere boeren een ceremoniële ‘kikkerbruiloft’ om de regengod gunstig te stemmen.

- Een verouderde irrigatietechniek is bijvoorbeeld met een gieter elke kool water geven.

- De sensor gaat eruitzien als een soort thermometer die boeren in de grond steken. Boeren krijgen signalen van de sensor via wifi.

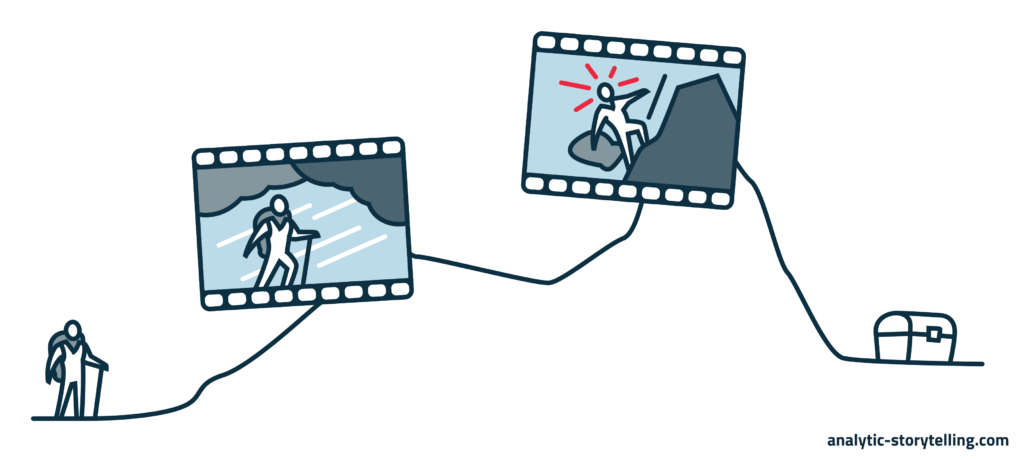

Stap 4: Maak tekst of beeld

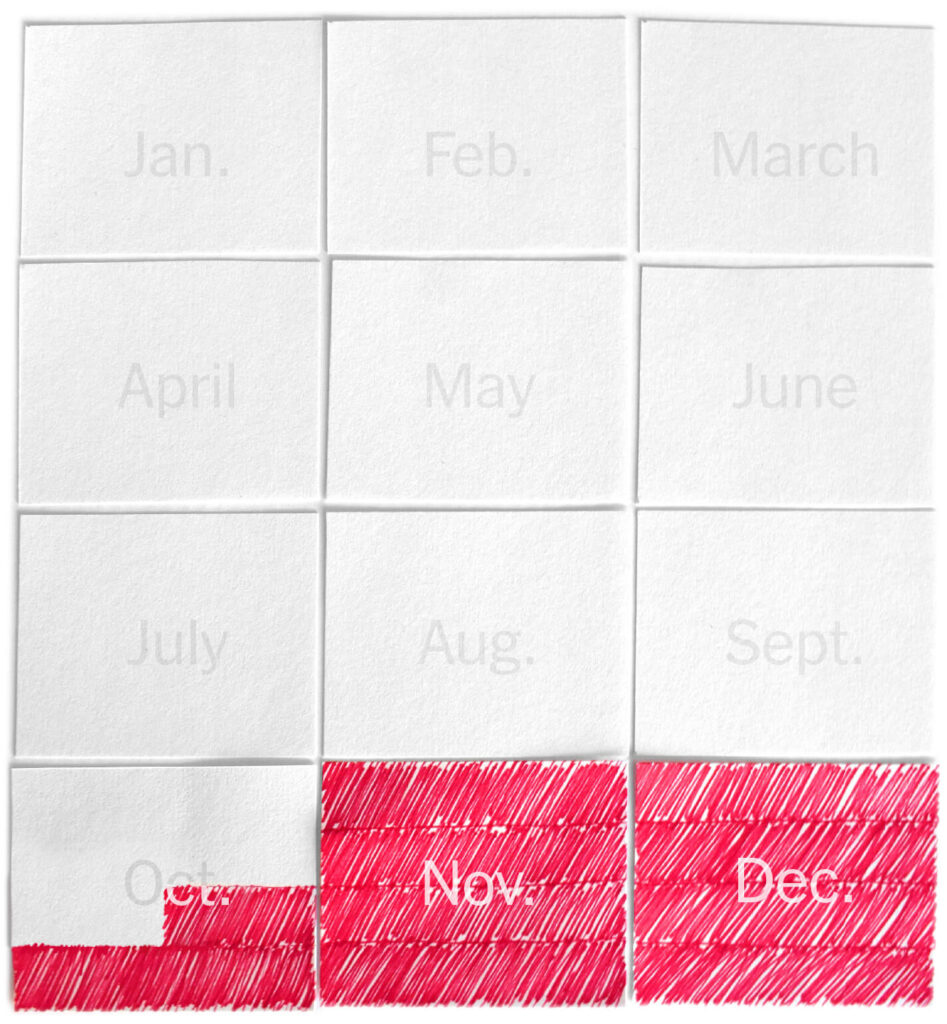

Uitstel heeft een negatieve bijklank.

Maar het is een belangrijk onderdeel van de Analytic Storytelling-methode.

Door de eerste 3 stappen, stel je het moment uit dat je ‘echt’ iets maakt.

Je zorgt eerst dat je een blauwdruk hebt van je verhaal. Bijvoorbeeld in een lijst met bulletpoints. En pas dan ga je aan de slag met je tekst of met beelden.

Door storytelling in deze 4 stappen ‘op te knippen’ versoepel je het maakproces. En tegelijk maak je je eindproduct beter.

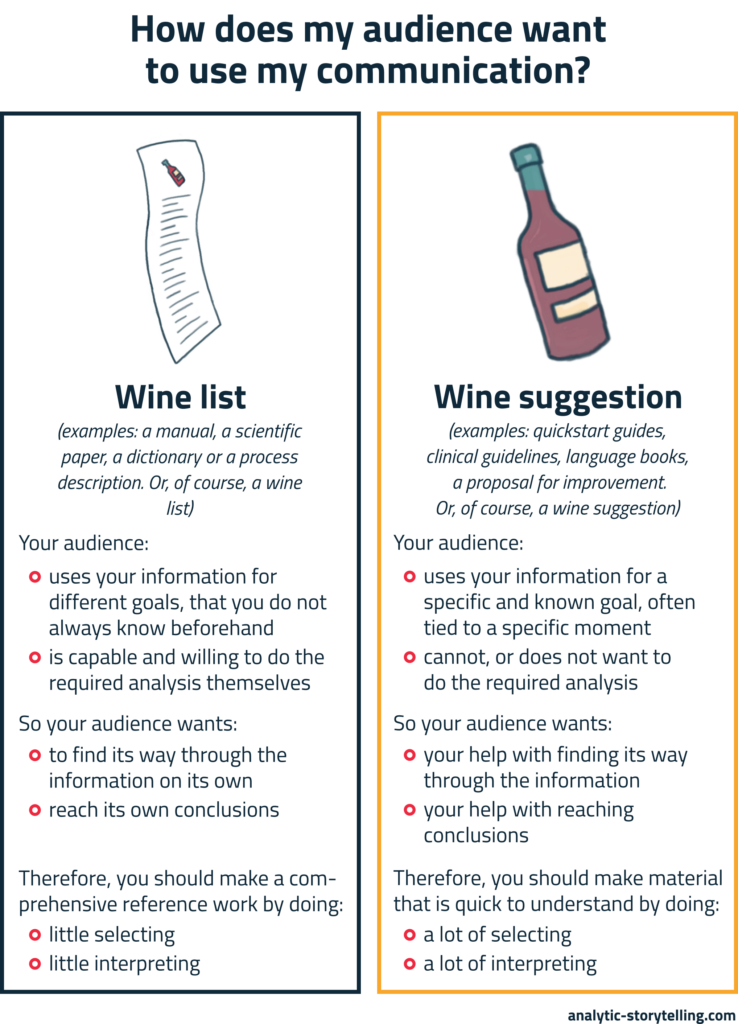

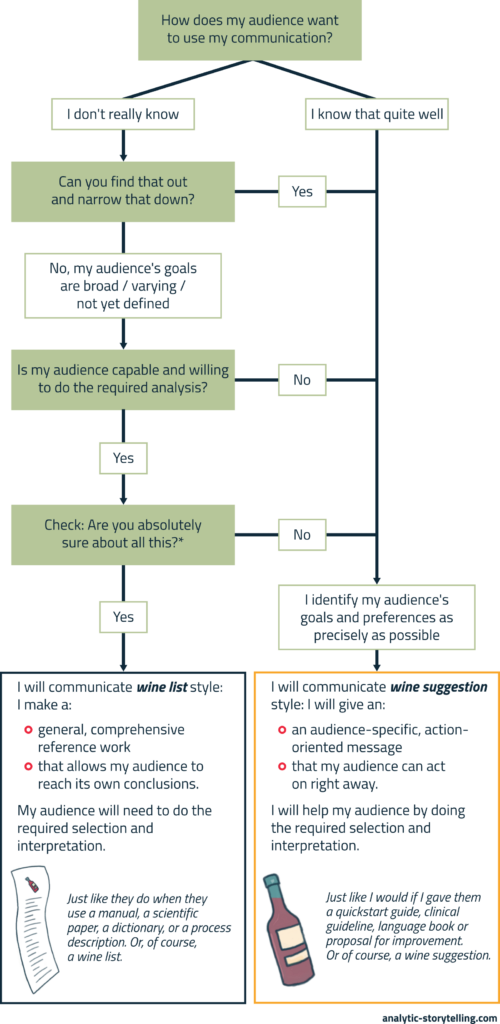

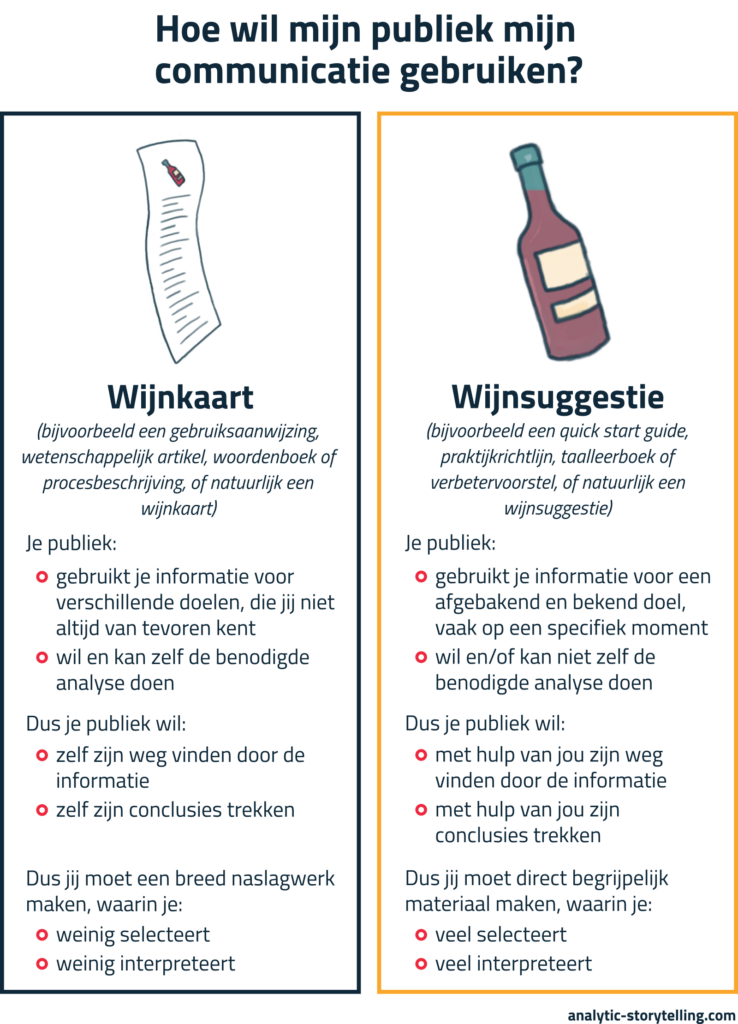

Ook in de laatste stap zijn er natuurlijk nog aandachtspunten: zowel voor tekst als beeld.

Het is bijvoorbeeld goed om te zorgen voor een duidelijke hoofdboodschap voor elke alinea of slide. En om te zorgen dat elk woord of elk beeld die boodschap ondersteunt.

Uiteraard zijn er nog veel meer aandachtspunten. Onnodige passieve zinnen vermijden, alinea’s niet te lang maken, met kleurgebruik en compositie laten zien wat belangrijk is… Over goed schrijven en goed visualiseren zijn bibliotheken vol geschreven.

Maar als je verhaal aangepast is aan je publiek (stap 1), een goede structuur heeft (stap 2) en goede concretiseringen bevat (stap 3), heb je de belangrijkste stappen al gezet.

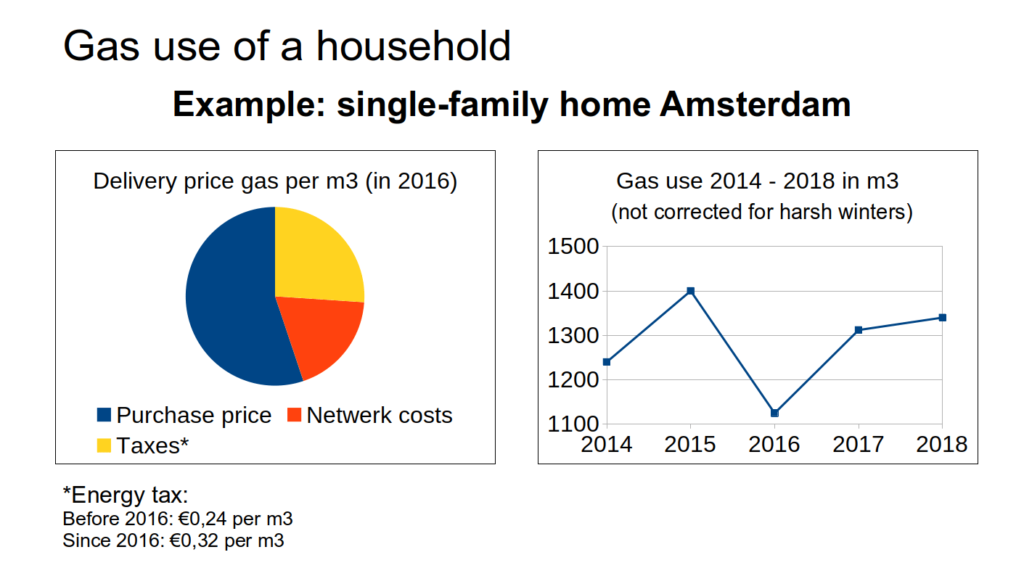

Laura maakt een presentatie.

Eerst formuleert ze de boodschap van elke slide. Een van haar boodschappen is bijvoorbeeld: Een sensor maakt duidelijk wanneer een gewas water moet krijgen.

Laura zoekt foto’s van een drukke straat in Mumbai, een supermarktschap met kool en aubergines en van het Indiase restaurant dat mee wil werken.

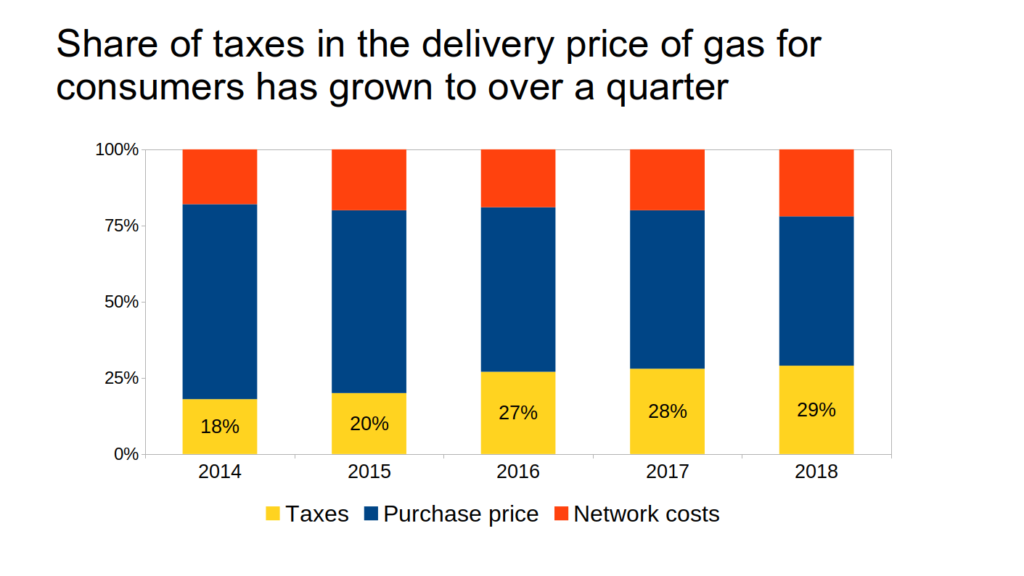

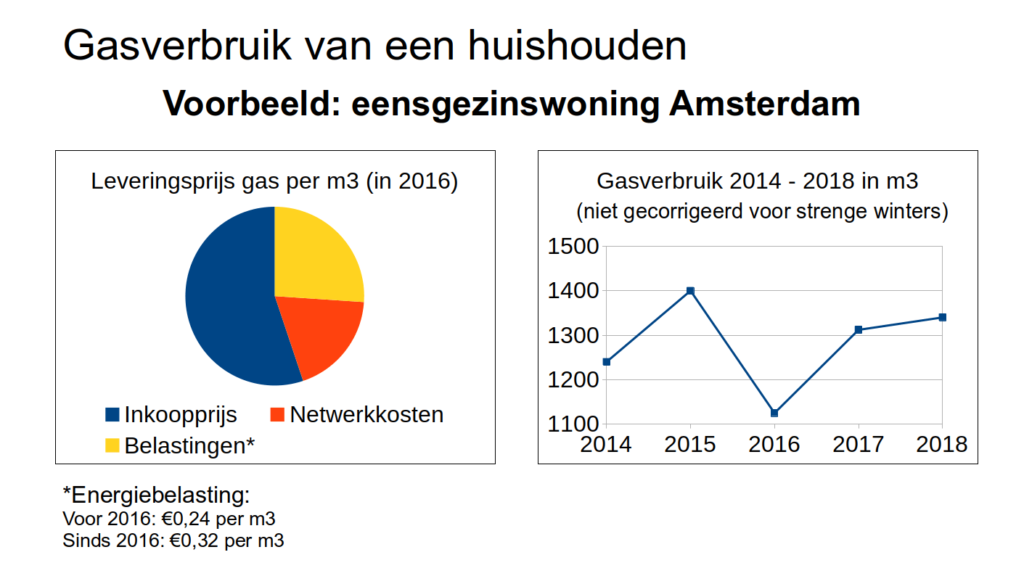

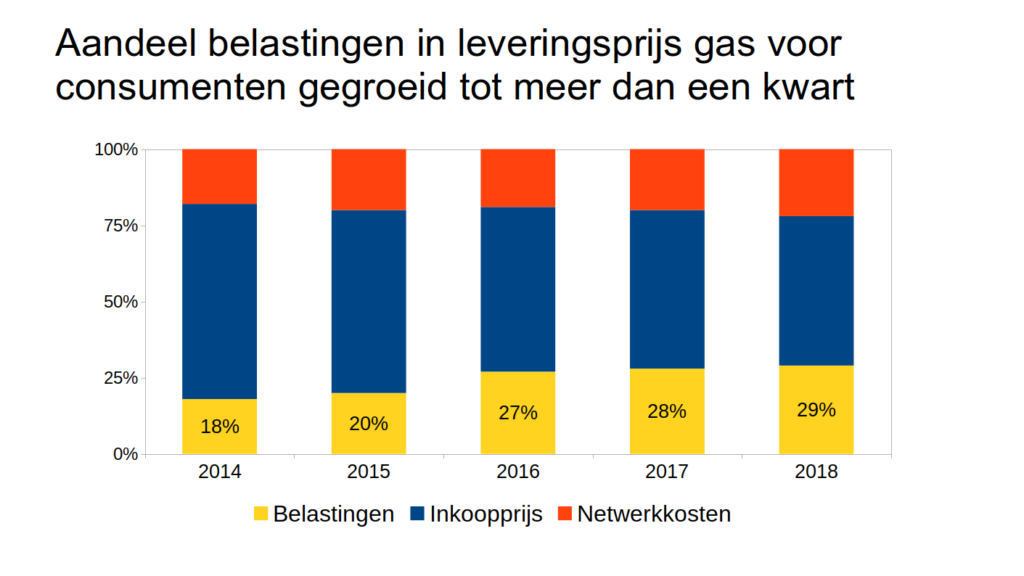

De heftige zelfmoordcijfers zet ze in een simpele, kale grafiek zonder onnodige waarden en rasterlijnen.

Ze heeft al een kort filmpje van boer Vyaan op zijn land met een gieter.

En ze gebruikt icoontjes van een thermometer, een batterij (daar werkt de sensor op) en wifi.

In een schema toont ze hoe de sensors kunnen worden verbonden aan een klein irrigatiesysteem met leidingen en kleppen. Sensors, leidingen en kleppen geeft ze een eigen kleur.

Stap voor stap naar een verhaal

De Analytic Storytellingmethode helpt je in 4 stappen van een eerste idee naar een eindproduct. Net zoals Laura in het voorbeeld.

Wil je de methode verder onder de knie krijgen? Dat kan in onze trainingen. Daar werk je aan een verhaal over je eigen onderwerp en leer je tegelijk storytellingtechnieken.

Heb je hulp nodig bij een storytellingproject in je organisatie? Mail of bel ons! We bespreken graag de mogelijkheden met je.

Arnaud is trainer, adviseur en tekstschrijver bij Analytic Storytelling. Hij helpt klanten om een heldere en overtuigende boodschap op papier te krijgen in woord en beeld.